Mind the involuntary observational learning

Today I want to talk about something that has been bothering me for quite a while now - the side effects of how we teach people to use frameworks, libraries, tools, …

It’s an issue I’ve observed a lot over the years. To the point I have somehow trained myself to immediately notice it when I see it. It’s present in conference talks, blogs, articles, video tutorials, code samples, … virtually any type of learning material that shows Java classes in packages. A lot of those materials are created by people whose knowledge and intentions are unquestionable. I’m full of respect for the great work those folks do. Yet I can’t help but notice how many of them involuntary introduce to young developers a very bad practice.

I really don’t want to be the moron who noticed something not quite right and is now rushing to criticize. Sadly my experiences shows people often feel this is the case when given negative feedback. So it’s been hard for me to point fingers at the (otherwise great) outcome of people’s hard work.

The observation

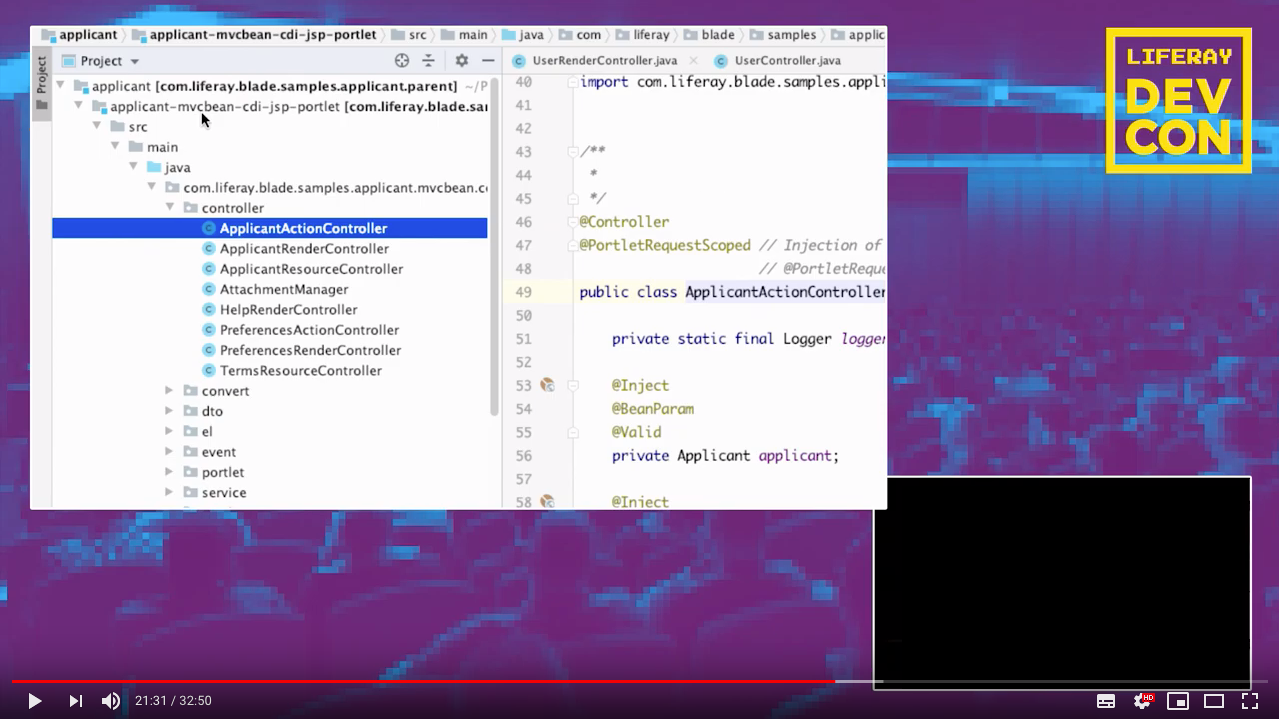

Here is a screenshot of the recording of otherwise amazing talk at Liferay DEVCON 2019 by a friend and colleague. Take a closer look at the structure of the source code displayed. Is there something that bothers you?

I don’t know about you but I get goose flesh when I see package names like those:

___.___.controller___.___.dto___.___.service- …

I’ve seen very similar structures in Spring, Jakarta EE, MicroProfile and even (shockingly) some OSGi tutorials, articles, posts, talks, …

The issue

I do understand where that comes from. Those materials are created to teach a particular technology. They concentrate on the actual code inside the classes. Where the classes are placed is irrelevant to the actual learning experience. Moreover grouping them this way makes it easier to the reader / observer to focus on particular phase of the learning path (“here we talk about controllers”, “here we talk about DTOs”, …). Of course the authors don’t promote nor emphasize such package structure. The assumption seems to be that everyone understands that what they see is just a demo code and people would somehow “do it right” in the “real world” case.

I would however argue that, an involuntary observational learning causes that, such examples make the wrong patterns stick inside people’s minds. Later on developers use them in production code convinced they follow a best practice as demonstrated by famous speaker or official tutorial. Then other people follow their example and the problem grows exponentially. This contributes to the fact that packages are likely Java’s most ignored, misunderstood and misused concept.

Wait, what’s wrong with that example

To understand why this is so wrong, imagine we don’t talk about packages but jar files instead. Imagine that you develop an application and you put all your controllers in one jar file, all your DTOs in another jar file, all your services in yet another jar file, … You get the picture. And it probably looks ridiculous and makes no sense to you, right? After all, those jar files will be so tightly coupled that you will almost always need them all together. Technically it would be no different from putting all of them in a single jar. The only thing the separation provides is some extra “jar chasing fun” to the person running the application.

It’s not any different with packages. Packages must always group classes in a coherent way. Packages in libraries must also provide strong encapsulation.

Packages should always be designed to appear coherent to the consumer (reader) not the producer. Back to the code on the screenshot above, if as a consumer I’m looking for say AplicantActionControler the coherence that I’m expecting is most likely “classes about applicants” and not “classes that are controllers”.

When we talk about libraries, a second dimension of segregation is needed. In addition to the coherence, packages should also hide internals and expose interfaces. While Java developers building OSGi based applications are well aware of that, many others only begin to discover the importance as they adopt Java Platform Module System (JPMS, a.k.a Jigsaw) in recent Java versions. As the adoption of JPMS increases, so will the need to package classes properly.

How to fix it

If I was preparing the above demo, my package structure would have rather been something like this:

___.___.applicant___.___.applicant.internal___.___.terms___.___.terms.internal___.___.shared___.___.shared.internal- …

I’d argue we should re-enforce the message about the importance of coherence and strong encapsulation on every occasion. No matter if it is tutorial, demo, PoC or production code. If we are serious about teaching people to write good code, we must take no shortcuts as those will inevitably be seen as patterns. I’d rather have people confused about my usage of packages and ask me questions about it, than have them assume it’s OK to just throw classes in a packages named after some (irrelevant from business perspective) technical characteristic.

It’s not only about packages

And it’s not only about bad examples. Missing context is almost as bad. Modularity for example is often ignored concept in many resources, thus convincing people it’s not important. Software architecture and application design suffer from the same side effects:

Just because we're not saying something in our talk, doesn't mean we don't think it's important.

— Andy Palmer (@AndyPalmer) December 6, 2019

People seem keen to read into what's not said - "they didn't explicitly mention design, therefore we shouldn't do design" @simonbrown #yow19

We kind of learned the lesson in the case of security though. Most content I see these days has some kind of warning stating that what you are looking at is just a demo/sample and is not secure the way it is. They often point out some potential risks and strongly encourage people to learn about security before they apply what they have just learned on production. Can we all please do the same for software architecture, application design, modularity, packaging, …?

I’ll conclude this post with a request to my fellow speakers, bloggers, technical writers, trainers and in general people who teach other people. When working on a demo/sample code, please watch out for patterns, or lack thereof, that predispose to involuntary observational learning of bad habits.